This blog addresses solutions that are fair, as well as touching on factors that go into deciding amounts, why that’s the case, and what models can do to their profiles to avoid being skipped over aside from not making common photographic mistakes.

It’s understandable that models would prefer paid shoots, but it’s also important to recognize that the photographer does as well.

For a model, the photo session ends with the last shutter click, but for the photographer that’s when the real work begins. This reveals why photographers can be so expensive. Add risk, like missing an important wedding moment, at the pricing tier jumps again to astronomical levels.

In all cases, I believe a model should be fairly compensated. The debate will boil down to what that compensation is and that expectation should always be spelled out up front before anything progresses.

There are many factors that go into what value compensation should be set at. There are three big ones.

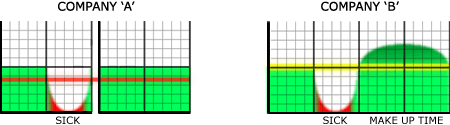

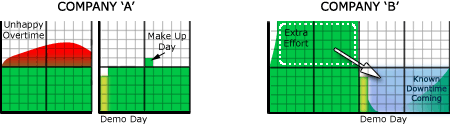

Expertise, in particular, plays a large part because an experienced model arrives on time (and sober), knows how to interact with the camera and the photographer with minimal direction, assumes appropriate poses naturally that fit the context of the scene, pauses at the right times as to minimize the number of discards, and she can make facial expressions look genuine. The higher compensation comes from making the photographer’s job easier and producing higher quality product in a shorter timeframe.

The model’s looks also play into the equation, primarily because that sets the demand for the model and in turn that affects availability. Basic economic models of supply and demand clearly state the higher the demand, the more things cost. Hence a model that isn’t in as much demand will likely be unable to command rates that one is. This is why models should to TFP deals to build their portfolios in order to raise their demand, even if just from gaining additional experience.

And the other primary factor which affects cost is how much skin the model is willing to show and what she’s willing to do in front of the camera. Unlike looks, this is one area where all models have total control. It can also be one of the bigger money makers.

The photographer has to determine a rate that factors these accordingly, and many other things (availability, short-term notice, …) as well into the compensation rate.

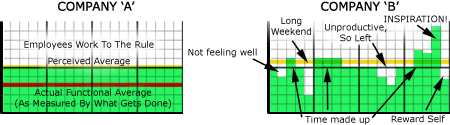

Just because both models are willing to stand in front of the camera for equal time does not mean they are providing equal value to the photographer. [It is also true that multiple photographers do not provide equal representation value to a model, which is why one looks at a photographer’s portfolio before accepting a trade-based assignment. Skill, equipment, and post-processing abilities are the parameters the photographer has to measure up to.]

Here’s a reasonable compensation paradigm that is actually fair to both parties equally:

- If a model is hired by the photographer, the compensation is cash. (Pose for me.)

- If there is a trade of services, her compensation is the photos and his the model’s time.

- If the photographer is hired by the model, the compensation is cash. (Make me a portfolio.)

This makes sense from other business methodologies: if you were hired to do a task, such as frame a painting, you get paid, you don’t get a copy of the painting, free frames, or free framing services. An expert framer, incidentally, would be paid more too, and the resulting craftsmanship would be obvious. Quality, not time, is what’s sought.

The task a photographer is hiring for is to have someone take specific direction so they can produce a precise product. To get cash and photos would be double compensation and thereby a double hit on the photographer; most likely that would be the last time the photographer ever cast or recommended the model.

That said, there is nothing wrong with the model requesting some pictures in leu of some portion of the cash. Sometimes the photographer can do this, but quite often if the photographer has been hired on behalf of client, it’s stipulated in the contract that he can not. Hence the cash, which usually comes from a budget that the photographer may, or may not, have control over.

If a model wants photos and tear sheets, that should be negotiated up front, not after the shoot. Again, the photographer may have contractual bindings.

Some models will be fortunate enough to find photographers who will give away photos in addition to cash. Models, if you get cash, don’t expect this, but be grateful if it happens to you — the photographer has figured out a win-win situation that you both can benefit from. Don’t be mistaken, this action is somewhat self serving to the photographer, as he’s looking for extra visibility and word of mouth advertising from you to widen his client base.

Paying gigs are more likely for models when the client needs a specific look. If there’s just a generic need, photographers are going to draw more from TFP/CD deals. Knowing this, the more variety a model can pull off in her portfolio, the easier she just made it for the photographer to just to cut a check than to keep searching.

There does seem to be a subset of models that have a higher impression of their own market value than the market will actually tolerate. New models don’t seem to have this problem much, experienced models have a very good sense of worth (and a portfolio to prove it), but it’s most common among the narrow my-portfolio-is-cell-phone-pictures / I-want-a-job-pay-me modeling-wannabes. These models are usually difficult to work with and are problematic after the shoot, having shifting expectations of the deliverable. Photographers will actively try to avoid them and anyone that fits that stereotype.

Models: if your portfolio reeks of indicators that you fall into this pile (whether you really do or not), be aware that you’re hurting your chances to get a casting call, profile comments, TFP/CD deals, and valuable experience. If you want higher compensation, simply do what those did who are earning it. Their profiles are right there in the open on many modeling sites. Your chances of getting directed casting calls will increase.